A conversation with Karen D. Taylor, founder of While We Are Still Here

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

October 10, 2020

New York City is constantly reinventing itself. As a port city, and financial and cultural capital, New York has evolved over centuries of migration and innovation. The South Street Seaport Museum was founded in part to share this story of “port-powered” reinvention, and we are far from the only group of people who are passionate about New York’s history.

Luckily, most of us working at the Seaport Museum get to talk to people who love New York City’s history, and one of my responsibilities as a collections staff member is responding to the many researchers that email us. Our collections and archives department receives numerous research requests from genealogists, students, historians, and authors of historical fiction, to people who just want to know the etymology of the term “poop deck”.

Though I love talking with each person that reaches out to the Seaport Museum, some of my favorite requests are from staff and volunteers at other cultural institutions here in New York. It’s an opportunity to connect with other museums, libraries, archives, and historical societies to pool together what we each know best about this incredible city.

This is how I met Karen D. Taylor, the founder of While We Are Still Here —an organization that preserves and honors the cultural history of Harlem in the face of rapid change and gentrification. I asked Karen if she would be open to being interviewed so I could share the work of While We Are Still Here (WWSH) on the Seaport Museum blog. Below are highlights from our conversation which touched on the importance of knowing your neighbors, the value of community voice in the telling of history, and how New York’s waterways connect us all.

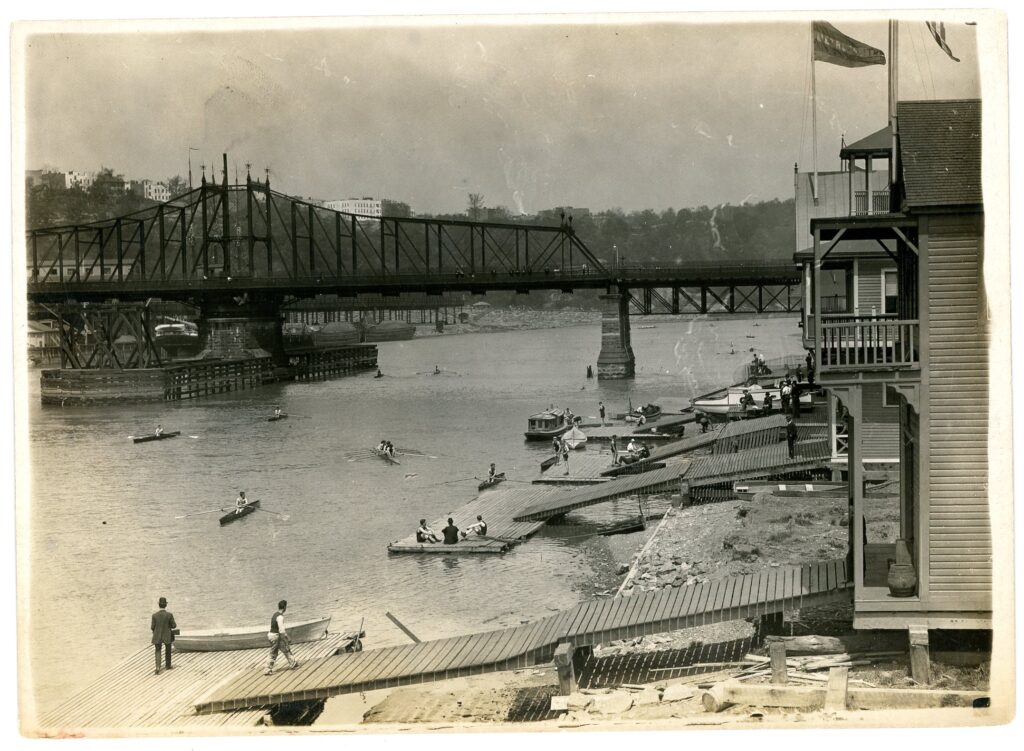

“Harlem River, looking upriver” ca. 1905. From the Jack Quinby Collection, South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H34-0016

Ms. Taylor is a longtime Harlem resident and the idea for WWSH started with her noticing that her new neighbors clearly had stories to tell: “I live at 555 Edgecombe Avenue and I moved here around 26-27 years ago. When I first moved here with my first husband I would see all of these really interesting people- elders- in the elevators and in the common hallways, and I said to him ‘There are these people around here, and they look really elegant like they were in show business or something.’”

The residents of 555 Edgecombe not only included musicians and actors in show business, but also entrepreneurs, labor organizers, and scientists. Ms. Taylor continued to learn of the people who had lived in her building: “I heard Paul Robeson lived in this building and that Joe Louis lived in this building, and that ‘Count’ Basie lived in this building— all of these very prominent people from the early to mid-twentieth century. So, I said what I’m going to do—and this was almost 30 years ago—I’m going to do an oral history with them.”

Ms. Taylor’s ambitious project took shape years later, and she was honest about the race against time that oral historians are all too familiar with: “I didn’t really start gathering the oral histories until around 6 years ago. It’s so unfortunate, and I can kick myself because I know so many stories died in this building. I know there were some women who lived here who were former dancers at the Cotton Club.”

As Ms. Taylor began to collect stories from 555 Edgecombe she learned of a sister building at 409 Edgecombe that was once home to more twentieth century icons: “W.E.B. DuBois lived down there, James Weldon Johnson, Thurgood Marshall..so I said to myself ‘Well, let’s just focus on 409 and 555 Edgecombe. That was original focus and mission.’”

The oral histories uncovered some amazing stories. One favorite Ms. Taylor mentioned was from Laverne Gaither, a 91 year-old resident of 409 Edgecombe who as a child knew her neighbor Thurgood Marshall: “He would help her carry her cello. She’s a musician and when she was a little girl going to her music lessons, he would see her with her cello and say ‘you’re a little girl- let me help you with that.’ And he’d carry her cello up to Amsterdam Avenue.”

409 and 555 Edgecombe Avenue from whilewearestillhere.org/about-us

Out of her oral history project Ms. Taylor founded While We Are Still Here: “We were founded in March of 2015 and essentially we started the organization because of the changing population in Harlem. There were more white people moving in and the African-American population was dying and/or moving, or being displaced and priced out. So we thought it was very important to try to codify the history, as much of it as we can, to try to get a taste of what Harlem’s history means.”

WWSH didn’t stop at collecting the oral histories of the two buildings; they ultimately created a documentary In The Face of What We Remember: Oral Histories of 409 and 555 Edgecombe Avenue which premiered at Columbia University’s Miller Theater, in 2018.

Though WWSH’s first mission was focused on the two buildings, identifying 409 and 555 Edgecombe Avenue as the epicenter of the intellectual, political, and artistic African American world in the early to mid-twentieth century, they soon expanded to tell the larger history of Harlem. In their About Us section on their website, WWSH explains that:

“…due to the input of our neighbors, we broadened the scope to include Harlem, in general. And in including more of Harlem, we seek to expand the panorama of its historical narrative, because the lens continues to be tightly focused on the Renaissance of the 1920s; the ravages of 1960s/70s-era drug addiction and dealing (and later, the crack epidemic); the crime and poverty; and now gentrification—but Harlem, in reality, is so much more than all of these things. We are not attempting to downplay or negate the realities of the preceding, but we are attempting to broaden the scope to include a perspective that reflects a resilient community of people, who lived, worked, thrived, and engaged in activities such as coaching little league teams, seeing to it that their children were educated, and who curated art shows in church basements and storefronts or on the sidewalk.”

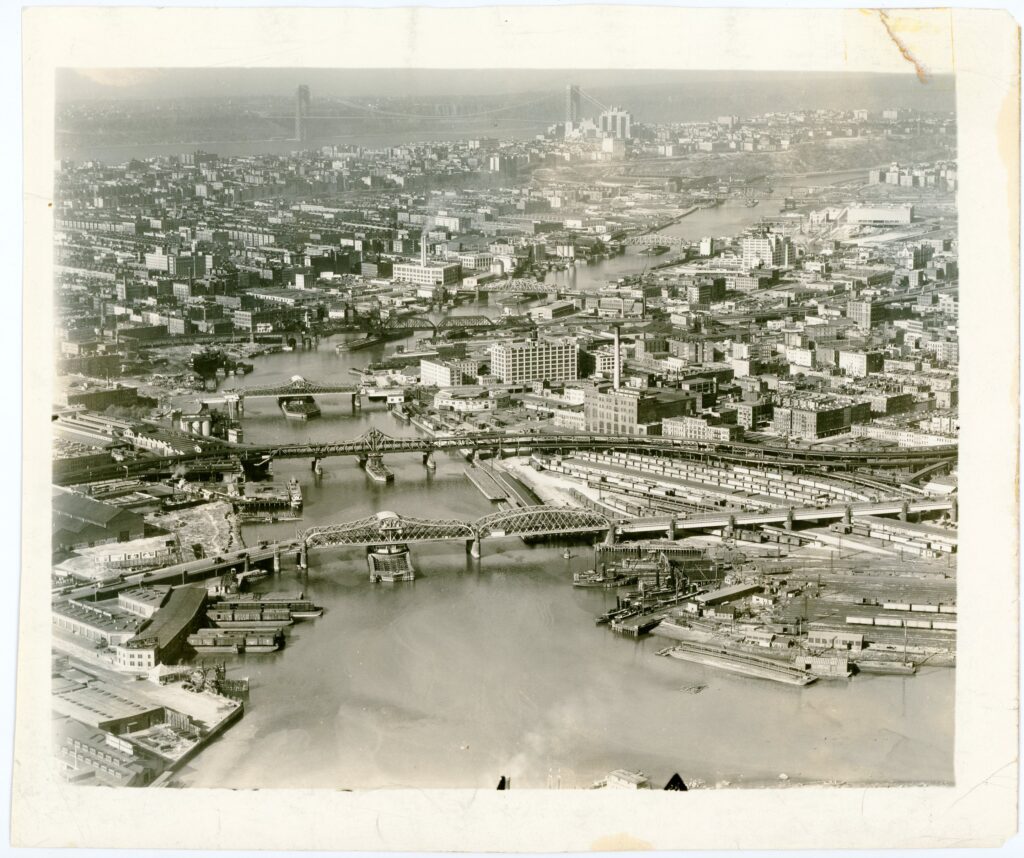

“Harlem River” ca. 1930s, by McLaughlin Aerial Survey. South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H34-0006

Covering the history of Harlem and the myriad ways it has contributed, and continues to contribute, to world culture is a tall order! As Ms.Taylor explained “It was overwhelming to think of trying to do this whole historical piece around Harlem, which is what we are attempting to do now.” Thankfully, there are people invested in the work of WWSH: “We’re lucky that we have many people who are professors, scholars and academics. Many of them have written quite extensively on Harlem history. Also, most of the people who are on our Board of Directors and Board of Advisors have lived in Harlem or still live in Harlem. They have this connection to the community that is very important for this type of work—especially the integrity of this work.”

It was WWSH’s expanded mission that brought Ms. Taylor to the Seaport Museum. When I asked her how she ended up contacting us she said it began with a community meeting. “In February [2020], we had a public meeting-—a town hall meeting—at the library at 125th Street. The purpose of the meeting was to get from people a list of historically significant sites for While We Are Still Here to have historic markers put up. We had about 25 to 30 people. One was Gale Brewer, the Manhattan Borough President, and another was her [Director of the Northern Manhattan Office] Athena Moore. People were giving us their ideas, writing their ideas on index cards and Athena is the one that put the seed in my head. She asked ‘can we figure out the points in which people came into Harlem during the Great Migration?’ and I thought yea, we know that some people took the train. We know some people drove their cars here. There were people who took the bus. So Athena inspired this curiosity I had.”

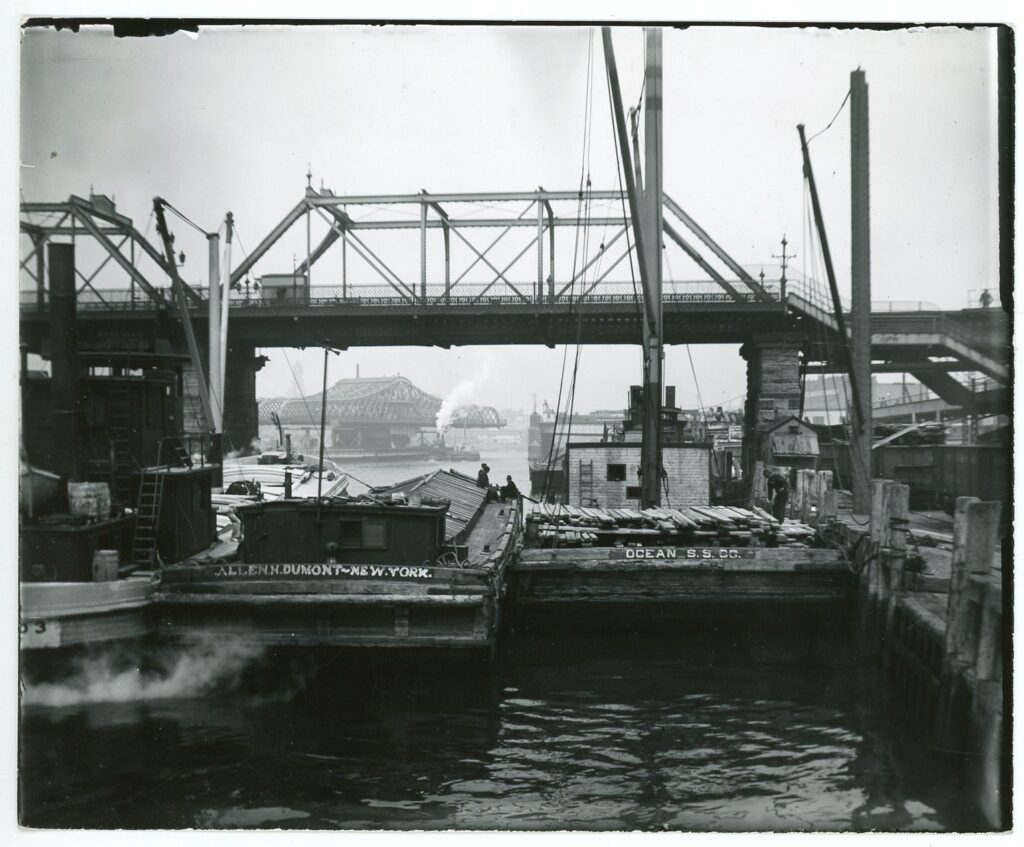

“Harlem River” April 30, 1910. South Street Seaport Museum H Photo Archive H34-0004

Ms. Taylor had come to South Street Seaport Museum to find the story of Black Americans moving to Harlem during the Great Migration (1915-1960) by ship. “One of the While We Are Still Here Directors, Vera Sims, had told me about her father. She said that her father came to New York from the Georgia Sea Islands and that he was a stowaway on a boat that came into Harlem. I was fascinated by that story.” Ms. Taylor’s interest was also piqued by the song “There’s a Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York” in George Gershwin’s 1935 opera Porgy and Bess. “There were boats that left from that region [around Charleston], came up the East Coast, and ended up in Harlem.”

After receiving Ms. Taylor’s email, I checked the Museum’s archives and collections for records related to the Great Migration from the American south. I didn’t find anything relevant in the first pass; the majority of material the Seaport Museum has on coastwise passenger travel during the mid-twentieth century is in the opposite direction— such as advertisements for cruises along the southern coast, to Miami, etc. In general, many of the documents and ephemera in our collections and archives were produced in New York for people already in New York. Though I didn’t find anything on the first pass, as Ms. Taylor’s research continues to develop, we’ll be able to take a second look through our holdings as the names of specific businesses, ships, and people are revealed.

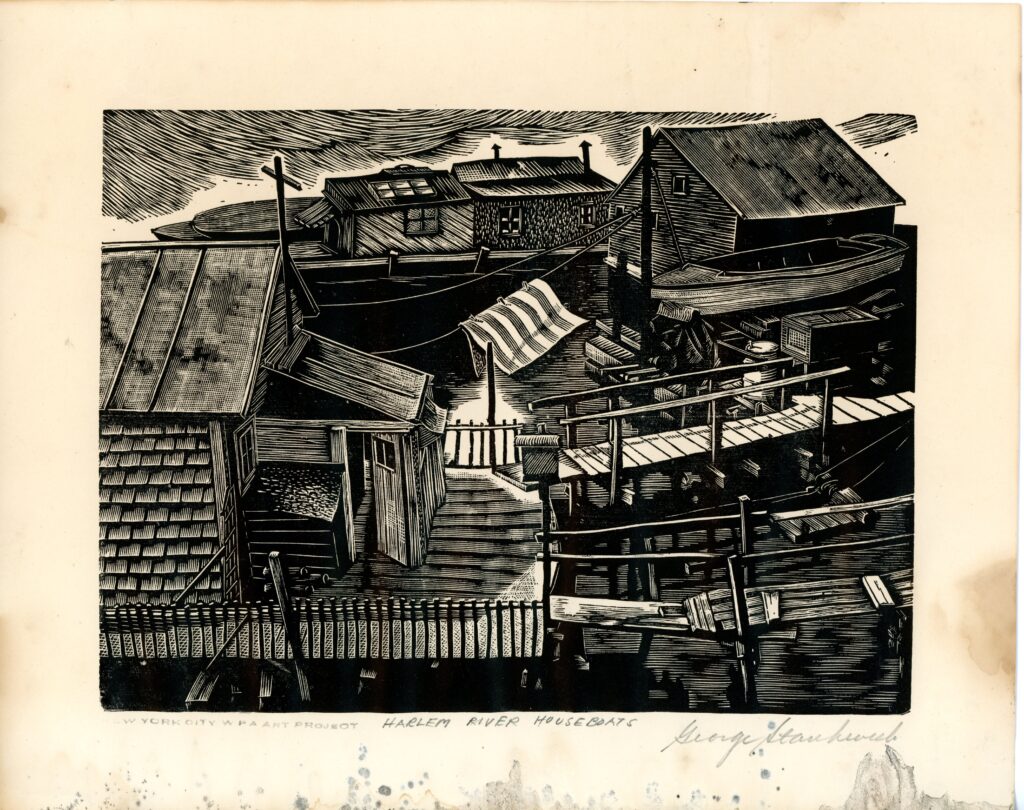

“Harlem River Houseboats” ca. 1935-1943, by George Staubach as part of the New York City Works Progress Administration (WPA) Art Project. South Street Seaport Museum 1988.090

Even though this research project is early stages, it underscores the connection Harlem has to New York City’s waterways with its waterfronts along the Hudson and Harlem Rivers. Ms. Taylor remembered how her own grandfather would travel by boat when he worked at Bear Mountain, NY: “He helped build what is now Bear Mountain. He was a laborer so he would go down to the piers and get on a boat to get up there.”

After speaking with Ms. Taylor about the history of Harlem and its waterways, I asked what she felt the future might hold considering both waterfront development and climate change. “Right now I am looking out at the Harlem River. I have a great view here. And on the Bronx side of the Harlem River you can see all this construction going on. I feel like I am looking into a crystal ball into what that waterfront will eventually be. In terms of climate change, for the people who live in the Harlem Valley, I could see it flooding. Now, I’m not a climatologist, but you can see that the water’s edge is right there.”

I’d like to thank Karen D. Taylor again for sharing the work of While We Are Still Here and the search for the intersecting stories of the Great Migration, Harlem, and the Port of New York. For me it is also a reminder that I never know what I’ll learn through the research requests that come into the Museum’s collection department inbox, and how it can broaden the understanding of New York City’s story, and strengthen the ties between all those who work to preserve that history.

Additional readings

“In Her Shoes: Walking through Harlem in Althea Gibson’s footsteps” by Karen D. Taylor, on March 29, published in espn.com, on March 29, 2019.

“The Sugar Hill Quartet to share their oral histories of St. Nick’s Pub at Bill’s Place” by Karen D. Taylor, published in Amsterdam News, on October 25, 2018.

“A Young Black Girl’s View of Harlem at the Height of the Great Migration” by Emily Raboteau, published in The New Yorker, on November 22, 2016.

“The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration” by By Isabel Wilkerson, published in SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE, September 2016.

“A Push to Preserve the Cultural Legacy of Harlem’s Sugar Hill” by By David Gonzalez, published in the New York Times, on December 13, 2015.

“Porgy and Bess. Gershwin’s quintessential American masterpiece melds jazz, folk, and gospel styles” The Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning, 1996-2020 John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.